AIDS activist’s sister found strength in struggle

Columbiana High School grad Holly?May does sign language for COVID-19 briefings in SC

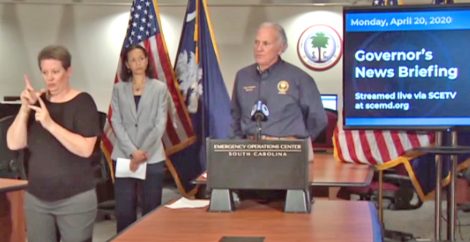

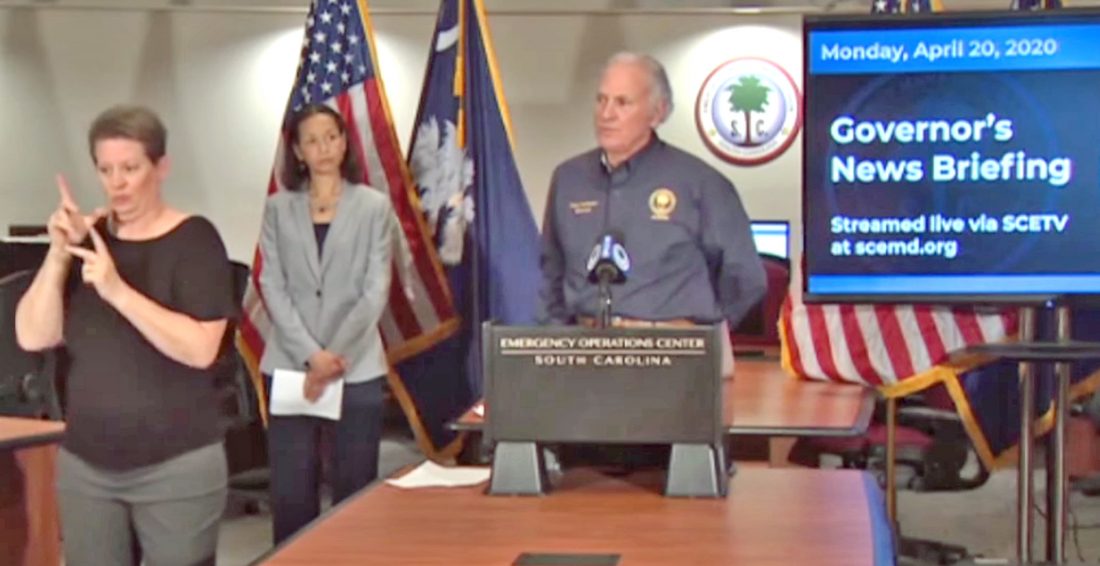

Columbiana High School graduate Holly (Blake) May, left, signs during South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster’s COVID-19 press briefing on April 20 in Columbia, South Carolina. (Screen capture).

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Around twice a week South Carolina Department of Mental Health Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program Director Holly May leaves the house that she shares with her three kids and husband to do sign language interpretation for Governor Henry McMaster’s COVID-19 pandemic press briefings.

The 1994 Columbiana High School graduate works on a team of two interpreters for the briefings (she’s the one with the short hair and no glasses). One appears on camera and the other stands off camera as potential relief if needed or to communicate missed details to the one who is on camera.

May has been signing for decades and relishes the challenge of working in disaster response even though it can get repetitive.

“When the media asks the same question over and over again it gets a little tiring but we forgive them,” May said. “I’ve been doing sign language enough over the years that it’s muscle memory at this point. My brain gets tired more than anything trying to go from one language to the other.”

Due to the importance of these briefings, a lot of folks are watching whether that be at the state level or nationally. So naturally she gets noticed.

HIV/AIDS activist Krista Blake, left, and sister Holly Blake pose for a photo in the summer of 1992. Likely HIV positive for four years already, Blake’s disease had progressed into AIDS by the time this photo was taken. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

- Columbiana High School graduate Holly (Blake) May, left, signs during South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster’s COVID-19 press briefing on April 20 in Columbia, South Carolina. (Screen capture).

- HIV/AIDS activist Krista Blake, left, and sister Holly Blake pose for a photo in the summer of 1992. Likely HIV positive for four years already, Blake’s disease had progressed into AIDS by the time this photo was taken. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

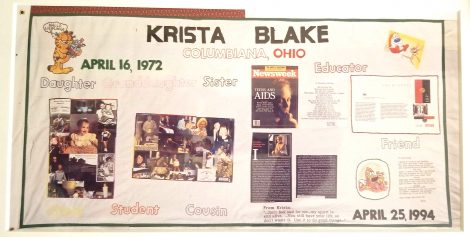

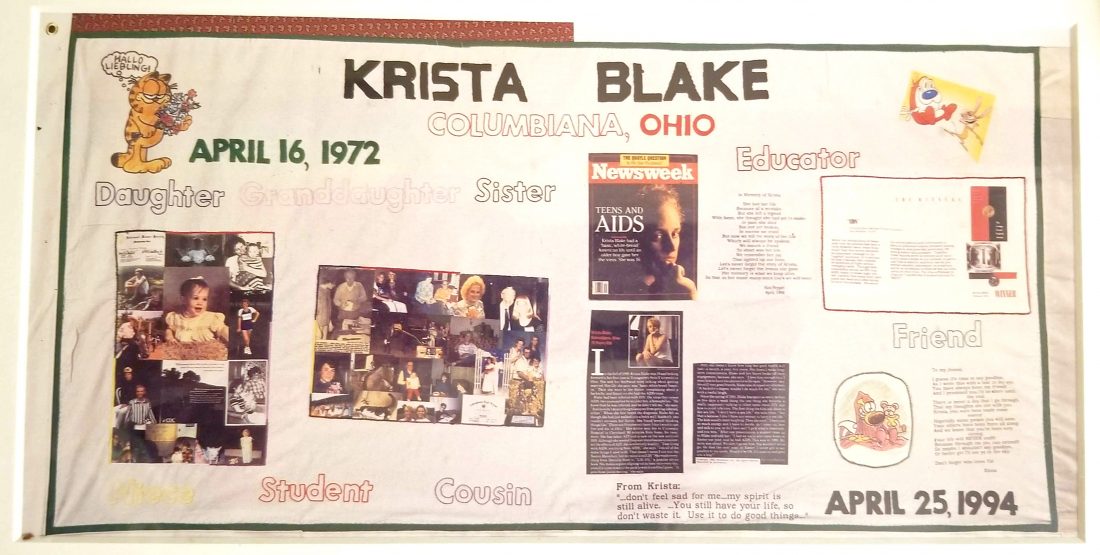

- Columbiana High School graduate Krista Blake’s Memorial AIDS Quilt panel was first revealed at Youngstown State University in the fall of 1994. Blake died of complications from AIDS on April 25, 1994 at the age of 22 in Cleveland. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

- the Blake family. From left, Erle, Krista, Dan and Holly pose for a photo in the summer of 1992. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

May could joke about her increased profile during these times, but she’s been here before. A lifetime ago, she was on the frontline of another global health crisis involving her sister Krista Blake.

——

In the fall of 1990, Krista was all set to start her collegiate career at Slippery Rock University. She had graduated 13th in her class at Columbiana High School and was a member of the National Honor Society.

May described her sister’s life as “average, run-of-the-mill small town Ohio girl.” Krista gravitated toward the academic side of things but was in the band and kept score for the baseball team. She also held some part-time jobs.

Columbiana High School graduate Krista Blake’s Memorial AIDS Quilt panel was first revealed at Youngstown State University in the fall of 1994. Blake died of complications from AIDS on April 25, 1994 at the age of 22 in Cleveland. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

But for the final two years of her high school career, something wasn’t right. Illnesses often sidelined Krista for longer than the family thought they should. She had mono at one point. Doctors perhaps thought she was worn down. The possibility of lupus was even thrown out there.

None of it added up.

“Finally a doctor said, ‘You know what? We’ve ruled out everything else, can I run this test?’,” May said. “She was 18 at that point but my parents were still really involved, so they agreed.”

The test came back positive for human immunodeficiency virus or HIV.

It was Oct. 11, 1990 according to testimony she later gave.

the Blake family. From left, Erle, Krista, Dan and Holly pose for a photo in the summer of 1992. (Photo courtesy of Holly May)

Krista was likely infected by having unprotected sex with an older hemophiliac boyfriend in the summer of 1988. The man later admitted to having HIV but did not feel it was important to share that with her before they had sex.

Her college career ended up never starting at Slippery Rock. She gave Youngstown State University a try for a bit but cognitive challenges and the growing need to tell her story sent her in a different direction.

“When we first got the diagnosis, being in a small town, it was kind of ‘who do we tell and what do we tell?’,” May said. “As a family we made the decision that there was a reason why this happened and we were just going to go public with it.”

Krista claimed she first went public with her illness when she told a professor at YSU in Jan. 1991.

Shortly thereafter she was in front of students telling her story and would remain doing so for more than three years.

——

May was a freshman at Columbiana High School when her sister was diagnosed. It changed the course of her life fairly quickly.

“It had some impact on my high school career, I think,” May said. “Being from a small town it was bad enough that everyone already knew what I was doing then you add that to it.”

May said her parents, Erle and Dan, had to often spend many nights with Krista in Cleveland while she got treatment. Because of that May had to stay with her best friend Jamie (Drexler) Hogan’s family.

“I was like their fourth child,” May said. “Cheryl and Dennis (Drexler) took me in whenever it was needed. There were no questions asked.”

In the hallways of Columbiana High School May said she was known as the “Condom Queen” because she would go to the county health department to get condoms and pass them out to whomever wanted them. She did not want any other family to go through what her own was taking on.

As Krista’s profile grew, so did the rate of May’s personal growth, for better or worse.

“(High school life) had its pros and cons,” May said. “I think I have always been a self-sufficient adult and that comes from having to grow up a little bit quicker and a little earlier than most folks. With that I gained a lot of wisdom, a lot of experience and a lot of exposure to the world that I don’t think I would have otherwise having grown up in Columbiana.”

May was sent to a therapist during that time and it ended up being so awful that it became career-defining.

“I would not have become a therapist if this did not happen,” May said. “When I was in high school my parents sent me to therapy and I don’t remember the therapist’s name, but I do remember that they were lousy. The person tried to tell me they knew exactly what I was going through and I can remember later thinking ‘How in the world can you know exactly what I was going through if you did not have a sister that has this exact disease?'”

While Krista’s disease pushed her in one direction, she saw a call-to-action in another arena that also was close to her heart. The Blake family matriarch was a longtime secretary at Joshua Dixon Elementary in Columbiana. May said that’s where Columbiana housed the deaf and hard of hearing program for the district. She said she became close to several friends in the program and decided early on that she wanted to be involved in helping the hearing impaired.

——

Krista Blake’s rise to becoming one of the most prominent young HIV/AIDS activists in the country was largely driven by her presence on the fledgling new in-school educational television network Channel 1. Launched in 1990, the network broadcast news throughout the country’s schools up until its demise in 2018.

One of the filmmakers involved in telling Krista Blake’s story for Channel 1 also made a documentary film about her entitled “Before I Sleep.” May still has a copy and shares it with anyone who wants to watch.

May says it’s rare these days that people remember her sister when she tells them about her. But if they do remember it’s because of the Channel 1 appearances.

In addition to appearing on smaller television and radio talk shows, Blake was further elevated in the national spotlight by appearing on the Aug. 2, 1992 cover of Newsweek magazine.

The article “Teenagers and AIDS” profiled several people from around the country struggling with the disease. Krista’s HIV had progressed into AIDS during that summer.

“I don’t really remember any reaction at all from Krista when she found out she was on the cover of Newsweek,” May said. “She was very humble.”

The piece explained the radical lifestyle changes Krista had to endure including breaking off an engagement with a fiance. It also shed light on her speaking style and how she did not hide from any personal questions about her disease when addressing students of the era.

“I don’t have a sex life but that’s because I don’t have any energy to have a sex life,” Krista was quoted as saying in the article. “I have just so much energy and I have to decide, do I come out here and talk to you, or do I have sex? I pick what’s important, and you won.”

May has carried on that spirit. When asked about whether it was possible her sister unknowingly spread the disease before she was diagnosed with HIV, May did not shy away.

“I believe she only had two other boyfriends during that time frame before she was diagnosed,” May said. “Obviously she had told them and to the best of our knowledge they were tested and were not positive. That was a relief.”

The family had to develop a tough facade in dealing with all of the speculation and gossip which came with Krista having the disease. May said they welcomed the burden and were equipped to handle it.

“It was instilled upon me that it didn’t matter what people thought of me, it was what I thought of myself that mattered the most,” May said. “As Krista and the rest of us would often say ‘If they’re talking about us, at least they were not talking about someone who could not handle it.”

May said the Newsweek cover is still displayed in her father’s house which is located on the same three acres of property as her own. Her mother Erle died in 2016.

——

May was only going to high school part time during her junior and senior years. Already enrolled at Youngstown State, she was taking advantage of a program that allowed high school students to complete college credits while still in high school.

This also served another purpose as Krista’s disease worsened.

“If she wasn’t feeling well enough to drive, I would be the one who would drive her (to her speaking engagements),” May said. “If my dad was off work, he would do it too. Towards the end when she started having some cognitive impacts from the medications, disease or whatever, we would do tag team presentations.”

May said Krista kept a busy schedule all the way up until a week or two before she was hospitalized with her final illness. Her immune system worn down by AIDS, Krista died on April 25, 1994 from pneumonia at University Hospital in Cleveland. She had turned 22 just nine days before.

The Blake family’s advocacy did not stop with Krista’s death. May said either she or her parents tried to fulfill as many of the previously scheduled speaking engagements as they could and that continued for a few years after.

In the fall of 1994, Krista’s panel on the AIDS Memorial Quilt was revealed at Youngstown State University. May and her mother sewed the quilt with assistance from the father. The quilt features the dates of her birth and death, her interests, quotations, photos of her, cartoon characters she liked and the Newsweek cover.

While on a trip scouting a potential graduate school in Washington DC in Oct. 1996, May said she was able to see Krista’s panel displayed with the entirety of the AIDS Quilt on the National Mall. It was the last time the entire AIDS Quilt was displayed in public. The 54-ton quilt is now too large to be displayed in full.

The numbers bear that out.

Since the start of the epidemic a total of 75 million people globally have been infected with HIV with 32 million having died. There are currently 38 million people globally who have HIV, including 1.1 million in the United States.

“I still hope people are out there hearing this story,” May said. “Even as far as long as we’ve come in research and treatment for the disease and the life expectancy it’s still not something that’s fun to live with.”

——

May graduated from Youngstown State in 1997 and moved away from the area to attend grad school before settling in South Carolina in 1999.

She is working from home these days except for the governor’s briefings and has been thinking about the common themes the COVD-19 pandemic and HIV/AIDS epidemic share. She notes that both diseases kill those with weakened immune systems but now there is a good amount of education being done to warn people of the dangers of COVID-19.

“They’re both scary,” May said. “People were dying from HIV because of lack of knowledge. Political views or whatnot aside, at least these days they are getting the education out there. There’s no judgement on people who are getting the coronavirus whereas back when HIV and AIDS were first brought in there was lots of judgement about people.”

Within her own family, “Aunt Krista” is still celebrated in the May household. Pictures of her are on the walls of the home and the children, ages 8, 12, and 16, were all told about her life from an early age (May insists all early conversations were age appropriate). As they grow older, May estimates the lessons of Krista’s life will become more important.

“She was your average teenager who just wasn’t educated enough to know how much she needed to protect herself,” May said. “She was able to put herself out there and hopefully save at least one person from having to go through the same thing. I think at least one person heard her and made different choices so their life didn’t have to end too early.”

mburich@mojonews.com